How much more can you see with both eyes instead of only one? Or in

case of astronomers, how much more can you see with a binoscope

compared to a traditional monocular telescope?

It has been a heated debate for years, especially after someone

published the idea on Cloudynights, the world's biggest astronomy

forum, that a binoscope performs only 1.18 times the diameter of a

telescope with one identical lens or mirror. In other words, the

difference between a traditional telescope and a binoscope would be

insignificantly small. Compare it to a C8 and a (hypothetical) C9.5.

The reasoning seems logical at first sight, because it's based

on the old binocular summation factor that was established by

Campbell and Green in 1965. Their study revealed that people have a

1.41x better light signal perception with both eyes, compared to only one. A 41% increase in perception matches a telescope with a diameter only 1.18x

larger and voilà: a binoscope is a ludicrous instrument that costs

an awful lot of money and is impossibly big and complex for a

miserable gain.

I found this idea rather strange because my experience, and that

of everyone else who’s looked through a binoscope, showed that the

difference between one and both eyes is quite significant.

So where do we go wrong? First of all, a binoscope captures

twice the amount of light as a monoscope, hence it should be equal to

a telescope 1.41 times the diameter. That's a significant difference that

would match my observations. Critics, however, cite Campbell and Green and therefore state that our brain

doesn't simply mix both images into one and that there's a

performance loss, resulting in only 1.41x more light gathering power

instead of 2x. How odd! If the light of both mirrors were transferred

to one and the same eyepiece, they would undoubtedly agree that in that

case the performance of a binoscope would double, compared to a

monoscope.

The critics go wrong because they misinterpret the Campbell and Green

study. This study was meant for medical purposes and has no bearing

whatsoever on an astronomical environment, i.e. in the total dark

when observing at the limits. Pirenne already demonstrated in 1949

that there's no such thing as a single binocular summation factor and

that results may vary greatly with different circumstances. Meese et al. demonstrated in 2006 that the binocular summation factor may even increase to 1.7x in certain circumstances. Unfortunately, as I said, all of these studies were being conducted for medical purposes and no-one seems to be interested in doing a study for an astronomical audience. However, they all seem to agree on:

- There is no such thing as a single binocular summation factor and

that summation improves when conditions worsen (Pirenne, 1949)

- The extent of summation depends on stimulus contrast and duration (Bearse and Freeman, 1994)

- There is significant summation at low contrast (Banton and Levi, 1991)

- At low contrast, the level of summation is greater than could be

expected by probability summation alone (Simmons and Kingdom, 1988)

- Summation depends on the complexity of the task, with simple tasks

(detection) displaying far greater summation than complicated ones

(pattern recognition) (Frisen and Lindblom, 1988)

In contrast, a lot has already been written on the subject on the popular astronomy fora, especially in endless and meaningless yes/no debates. But what

does real experience tell us? Obviously, it would be impossible to do

a comparative limiting magnitude test because which stars would you

use as a reference? And what does “I've seen it” mean anyway?

You've seen it or you think you’ve seen it? Such comparisons would

never have any real scientific value unless you involve many people

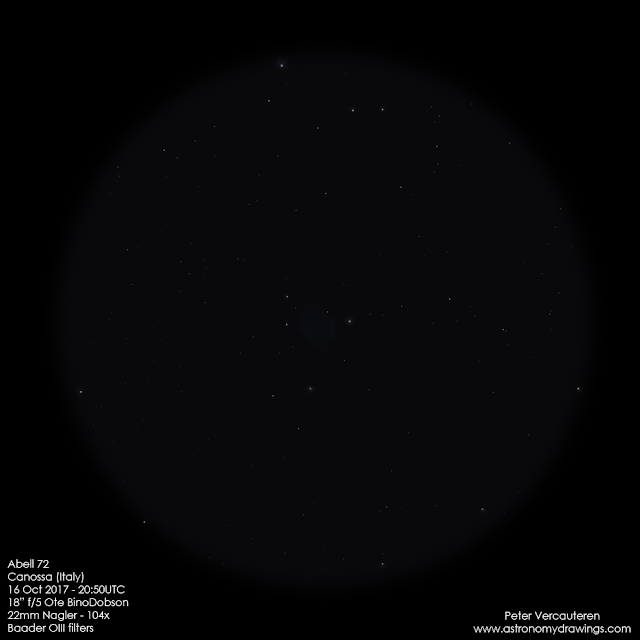

and then take an average. I know that "impressions" don't mean much, but the difference with

closing one eye is simply too great and certainly much more than the

hardly visible 1.19x. Faint stars for instance suddenly disappear or

become very hard to see. With both eyes M104's dust lane suddenly

appears full of structures, which fade to a dark band with monocular

vision. With both eyes I see the Pillars of Creation in M16, whereas

they're invisible with one eye (under my SQM20.9 sky and with my eyes).

Nebulae appear so much brighter and richer in detail, faint galaxy

clusters suddenly become easy, "impossible" objects such as the

extremely faint planetary ARO215 suddenly become possible... An aperture

increase of only 19%? Nah, I don't buy it.

Another, even more controversial statement is that a binoscope not only offers a significant light gain, it also increases resolution. Well,... yes and no. Unfortunately an amateur binoscope doesn't work like professional compound telescopes such as NASA's Large Binocular Telescope. Each of my 18" mirrors delivers the resolution of an 18" and our brain isn't capable of extracting a higher resolution from both images. However... it does work the same way as photographers stack various images in order to extract more detail, up to the technical resolution limit of their instrument.

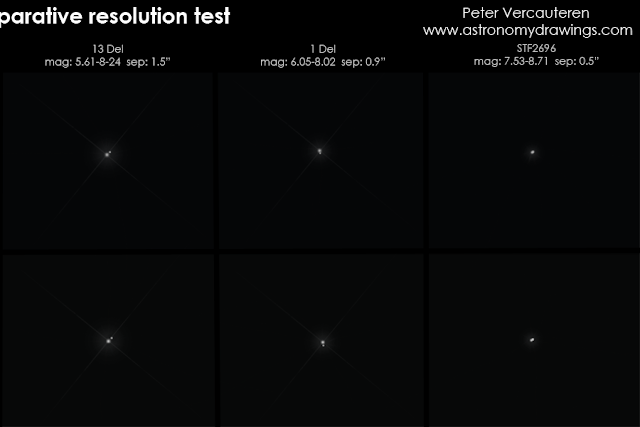

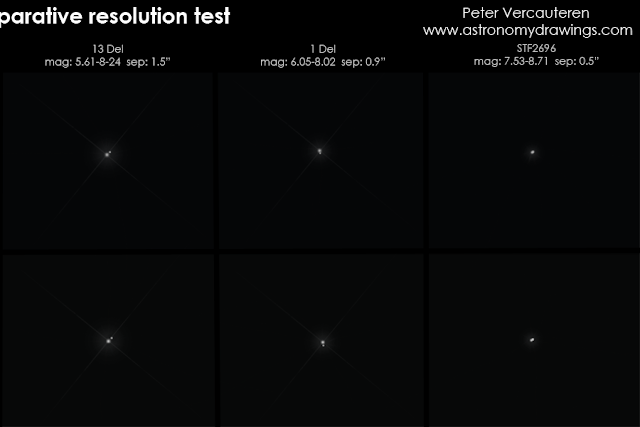

In order to demonstrate this, I’ve conducted a small experiment.

The other night the weather gods were in my favour because transparency was high and seeing was deliciously calm. I rolled out the binoscope and pointed it at a couple of double stars, some of which are

very close to one another. First, I used monocular view, in order

not to be biased, and then changed to binocular view. The results were astonishing. As you can see

on my sketch, the difference between a single 18” telescope and an

18” binoscope became ever more important as the two components

of the double star were closer to one another. 1 Del is pretty close with its separation of 0.9 arc-seconds, but binoscopic vision showed more black between both components than monocular view.

STF2696 was even more interesting. It is only 0.5 arc-seconds apart, which is very close to the 0.31 arc-second Rayleigh

limit of an 18” telescope. With one eye, I could only see one, elongated star, suggesting that it is a double without really being able to resolve it. With both eyes, on the other hand, both stars were clearly resolved and appeared to be glued to each other. The technical resolution of an amateur binoscope may not increase compared to an instrument with a similar single mirror, but this observation nonetheless confirms that binocular vision makes it easier to observe up to this technical resolution limit and that it will cancel out a large part of inhibiting factors such as atmospheric turbulences.

Of course, this was only a small, personal experiment and I will never pretend that it has any scientific value because, again, for that you'd need a lot of people of which a vast majority would have to confirm the same thing. But as far as I'm concerned, I'm convinced and will now leave the debating to others while I have some star gazing to do.